Dear Reader,

World Earth Day (22nd April), with an official theme of Planet versus Plastics, offers me an opportunity to merge my professional endeavours with my passion for geoscience. As some may know, I work as a communications consultant with #BreakFreeFromPlastic by (week) day, and as a geoscience communicator after-hours. This year's Earth Day theme emphasizes the urgent need to reduce plastic production, particularly single-use plastics. It recognises a strong global plastics treaty as a vital advocacy tool, which can address plastic pollution and prioritize human health.

Image credits: EarthDay.org

As a plastic pollution communicator, the greatest challenge is creating awareness through science to catalyse action, over a topic that leaves people feeling helpless or overwhelmed. To complicate the matter further, we often need to counter misinformation propagated by the petrochemical industry, which has sown seeds of doubt, or worse still, blunted the sense of urgency and the distributed responsibility needed to tackle the problem. Science can serve as a reliable compass if we can effectively discern fact from fiction, and real solutions from greenwashing.

As there are numerous resources on plastic pollution out there and the Earth Day theme would spawn a lot of coverage on the impact of plastics, I'd like to focus on how the issue of plastic pollution intersects with geosciences and can offer opportunities to study human impacts on the Earth's surface processes, ecosystems, and geological history.

Plasticene - can plastics herald the Anthropocene?

The term 'Plasticene' serves as a theoretical framework for a geological epoch characterized by the widespread presence of plastic in Earth's geological record. Unlike the Anthropocene (Read: Anthropocene - are we there yet?), which encompasses various proxies for human industrial activity, the Plasticene focuses specifically on the pervasive impact of plastic. Some scholars consider the Plasticene as a distinct era within the Anthropocene. The debate over accepting the term 'Anthropocene' persisted throughout February and March, with geoscientists remaining divided on the issue. (Read: Why did geologists reject the “Anthropocene” epoch? It’s not rock science.) While I'm not advocating for the official adoption of the term 'Plasticene,' it provides valuable insights into the distribution of plastics across diverse environments and ecosystems.

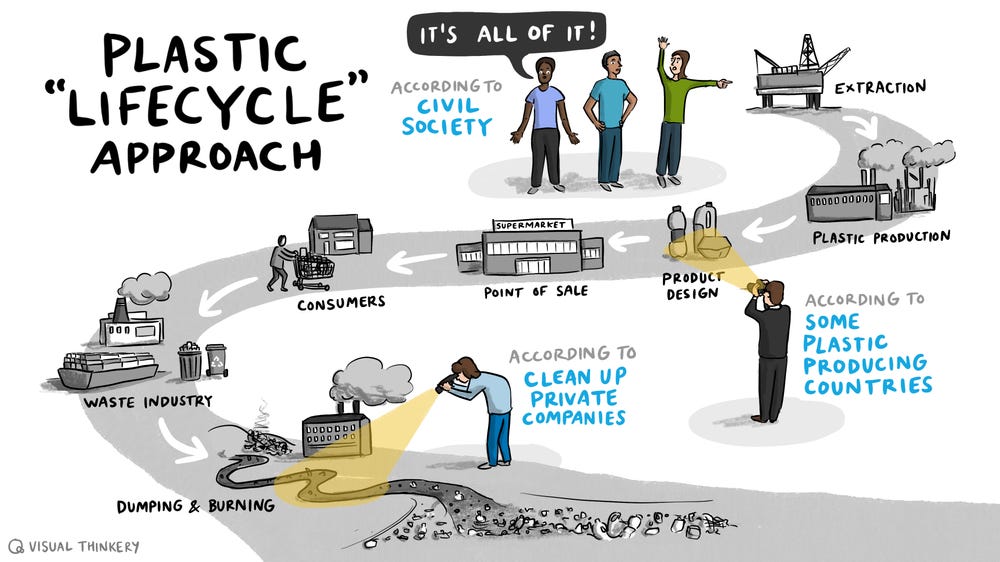

Image credits: Visual Thinkery, and courtesy of #BreakFreeFromPlastic.

Plastics, from the initial extraction of fossil fuels to manufacturing and consumption, are a quintessentially anthropogenic by-product of human activity. Polymers, the building blocks of plastics, are synthetic compounds created through chemical processes, quite unlike any natural minerals or materials in the geological records. Throughout the lifecycle of plastics — from the extraction of raw materials like oil and gas, and processing into a diverse array of products used in everyday life, to the accumulation in landfills and oceans — humans play a central role in driving demand, production, and disposal of plastics, and its distribution should help us document the Anthropocene.

Discarded plastics have been found on land, in lakes, rivers, and even in nearshore and offshore marine habitats, at the top of remote mountains, in the abyssal depths of oceans, where they are buried in sediments. The contamination extends beyond natural environments, with plastics infiltrating flora, and fauna, often crippling how they perform key ecosystem functions, and even entering human bodies. As plastic takes anywhere between 20 to 1,000 years to decompose, and even then, they do not completely biodegrade, these long-lived, plastic-laden sediments could be used as markers of the age and character of the deposits, much like how geologists use fossils to characterize and date rock strata. As plastics have also been transported across the solar system by spacecraft and deposited on celestial bodies like the Earth's moon and Mars, their potential as indicators of human impact stretches into space.

For those who'd like to read more, here's a paper on how plastics can serve as stratigraphic indicators of the Anthropocene, by Zalasiewicz et al (2016).

The Plastic Lexicon: Moulding New Vocabularies

As we experiment with creating different kinds of plastic, and fashion it into myriad products, we're seeing new terminologies emerge in fields from fashion to economics, popular culture to science. In geology, these may represent the materials, their physical or chemical properties, or a novel kind of landform.

Technofossils and microfossils: some researchers consider plastics as 'technofossils'. Technofossils represent human-made materials that will persist in the geological record long after their initial use. Plastic particles less than 5 mm in size, or microplastics — found virtually everywhere, including remote regions such as polar ice caps and deep-sea sediments — can also be considered as microfossils. Both technofossils and microfossils, like natural fossils, provide evidence of past human activities and environmental conditions, and can be used to understand historical patterns of plastic pollution and its effects on marine, riverine and terrestrial ecosystems.

Nurdles or mermaid's tears: Nurdles, or plastic ‘pellets’, are tiny granules of (virgin) plastic less than 5 mm in size used in industry to manufacture all kinds of plastic products. Classified as a specific kind of microplastic, nurdles or mermaid's tears, as some wordsmith termed it, along with textile fibres and tyre particles, are among the most common microplastics found in the environment.

Plastiglomerates: Plastiglomerates are a type of sedimentary rock composed of a mixture of natural materials (such as sand, rocks, and shells) fused with melted plastic debris. These formations occur when plastic waste is exposed to high temperatures, often from human-induced fires, which melt the plastic and fuse it with surrounding sedimentary materials. Plastiglomerates represent a new type of anthropogenic rock.

Pyroplastics: Pyroplastics are plastic materials that have been altered by exposure to high temperatures, typically through processes like combustion or melting. This term is often used to describe plastic debris that has undergone pyrolysis, a chemical decomposition process in the absence of oxygen. Pyroplastics can include a variety of plastic items, such as bottles, bags, and packaging, that have been transformed by fire or other heat sources.

Plasticrusts: Plasticrusts are a type of crust-like formation that develops on the surface of rocks and other substrates in coastal environments. These formations are the result of weathering and degradation of plastic debris, which creates a thin layer of plastic material adhering to the substrate. Plasticrusts are often found in areas with high levels of plastic pollution, where plastic debris is exposed to weathering processes such as sunlight, wind, and wave action. They represent a visible manifestation of plastic pollution and its impact on coastal ecosystems.

Searches on research sites yield numerous papers documenting the consequences of plastic pollution, its impact on human health and the emergence of novel landforms resulting from it. Occasionally, stories surface about plastic islands harbouring unique forms of life — which are best tempered with studies on the pervasiveness of plastics and associated chemical additives in the human body, from blood to brain. Synthetic plastic was invented as recently as 1907 and became widespread in the early to mid-20th century. Despite the relatively short time since its invention, research is gathering crucial evidence for the unprecedented impacts of plastics. It's time we took heed.

The Lego Drift: what clues lie in plastic toys lost at sea?

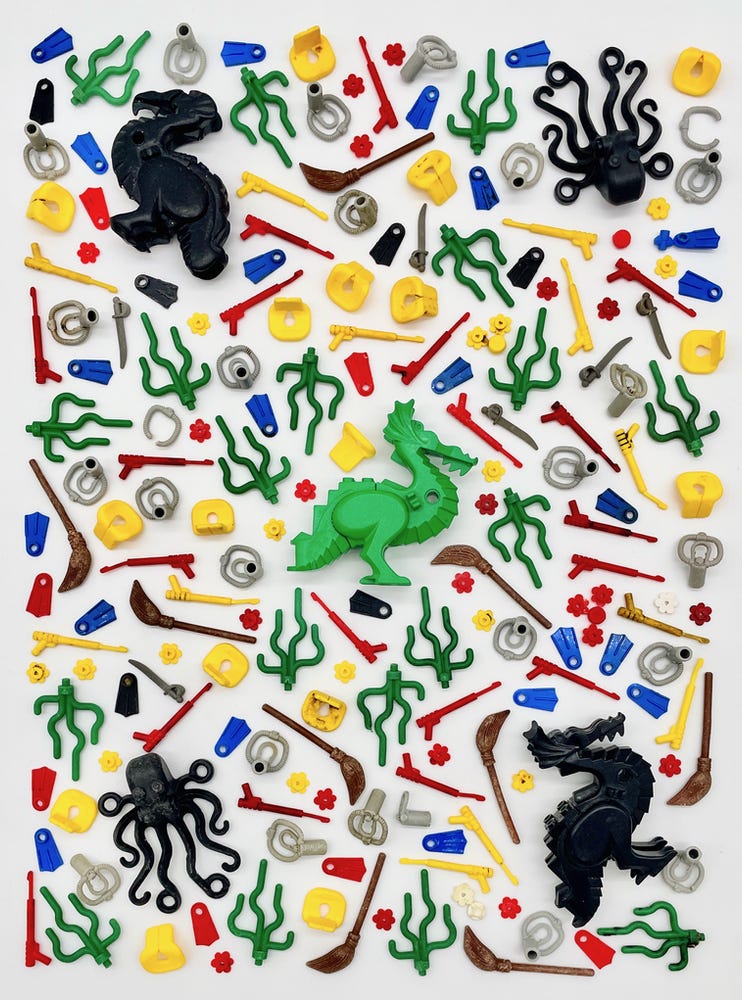

In 1997, a storm off Land's End, a cliffside vacation spot in Cornwall, west England, resulted in a million-piece cargo of Lego pieces being washed ashore. The cargo — a significant portion of which was marine-themed — was on its way from the company's factory in Billund, Denmark, to North America. Imagine flotsam of plastic dragons, octopi, sea grass, tiny divers' fins and scuba tanks, and even little bright-yellow lifejackets, tangled up in seaweed and driftwood, waiting for a sharp eye to rescue them? Cornish beachcombers, have long been collecting, cleaning and cataloguing these lost Lego pieces, and creating a buzz about them on social media with colourful photos. Someone also wrote a book titled Adrift: The Curious Tale of the Lego Lost at Sea, and interestingly, documents the recovery of these toys as an archaeological adventure (@LegoLostAtSea on Twitter, if anyone is interested).

So, can studying and cataloguing plastic toys be considered 'archaeology'? I loved this article, Archaeology Adrift?: A Curious Tale of Lego Lost at Sea which argues why this incredible citizen-science project should be considered as archaeology.

For the past ten years, The Great Global Nurdle Hunt has been documenting the occurrence of plastic pellets, with grim but important results: nurdles have been found on every continent, except Antarctica. This project too, should stake its claim as an 'archaeological study', and hopefully, will pave the way for plastic to be used as a proxy for human impact.

Beyond Plastics: The Toxic Footprints of the Plastic Industry

Beyond measuring plastics in the geological record, the plastic industry leaves behind several other signatures of damage and destruction. Extractive petrochemical factories or refineries, landfills and dumpsites, and highly polluting incinerators or waste-to-energy plants, spew a cocktail of toxic chemicals into the environment, causing serious impacts on human health and livelihoods. Here are some stories from frontline communities, who often pay the price of 'cheap, convenient plastic', and our plastic-dependent economies:

This #EarthDay2024, let's commit to comprehensively understanding the far-reaching impact of plastics on our planet, spanning geology, economics, social sciences, health, and human rights. While the Age of Polymers may seem entrenched, it's crucial to recognize that we've only been living with plastics for a few decades — the blink of an eye in geological history. The solutions to combat plastic pollution exist, from phasing out single-use plastics, to implementing refill and reuse models for distribution models, while steering clear of false solutions like chemical recycling, incineration, waste-to-energy, shipping of waste to less-developed economies. What's needed is a collective effort to distribute the responsibility of adopting and enforcing these solutions. By working together—governments, industries, communities, and individuals—we can still reverse the tide of plastic pollution and create a healthier, more sustainable future for our planet.

From April 23rd to 29th, 2024, the fourth round of intergovernmental negotiations for an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, the Global Plastics Treaty, will convene in Ottawa, Canada. This is our moment to take action as concerned citizens, communities, and scientists. Let's join hands with environmental and social justice organizations to advocate fiercely for a robust Global #PlasticsTreaty—one that is free from dilutions and delays caused by petrochemical lobbies. Stay tuned, or take action:

RELATED POSTS

#19: Anthropocene - are we there yet?

#21: Human Migration - Reflections on International Archaeology Day

Thanks for this Devayani! Some links seem to be missing though, for the stories on toxic footprints of the industry. Don’t know if it’s just me or if others can see them